Champagne, perhaps more than any other wine region in the world, is recognized for its high-profile luxury brands. Grande Marque (essentially “big brand”) houses like Veuve Clicquot, Moët & Chandon, and Louis Roederer are familiar to just about anyone who has ever celebrated with a bottle of bubbly. However, if one looks more closely, Champagne is comprised of an elaborate infrastructure of grape growers, family-owned wineries, and even cooperatives.

Yet, understanding who makes what, and how, is much easier than one might think. The first step is recognizing the three major categories of producers. All you need to do is look for the fine print on the label; a set of two-letter abbreviations will let you know in which category your Champagne belongs. The three most significant abbreviations are outlined below.

NM (négociant manipulant)

These producers buy fruit from independent growers to produce their wines, although many of them maintain their own vineyard holdings in addition. Most of the larger Champagne houses, including Les Grandes Marques, fall into this category. You can identify a producer as a négociant manipulant by the letters NM written in fine print.

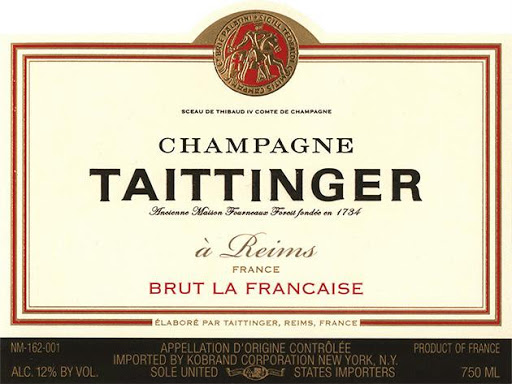

Examples of NM producers in Champagne: Krug, Bollinger, Ruinart, Veuve Clicquot, Perrier-Jouet, Jacquesson, Fleury, Taittinger

An example is Taittinger shown below. Note the term NM in the bottom left-hand corner of the label.

RM (récoltant manipulant)

The wines in this category are commonly referred to as grower-producer Champagne. These producers may only use a maximum of 5 percent purchased grapes in the production of their wines; at least 95 percent must come from their proper vineyard holdings. These bottles will have the letters RM written in fine print.

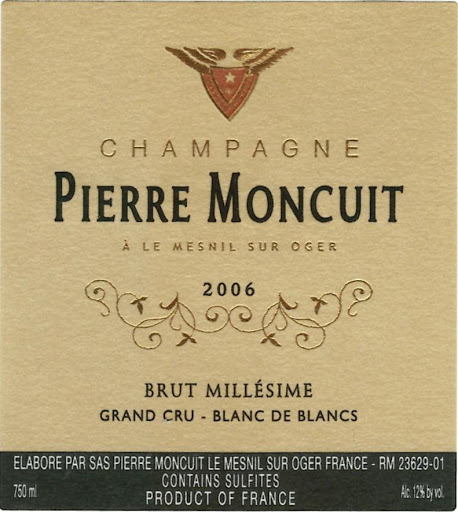

Examples of RM producers in Champagne: Bruno Michel, Franck Pascal, Georges Laval, Pierre Moncuit, Marie-Courtin, Ulysse Collin

An example is Pierre Moncuit shown below. Note the term RM in the bottom right-hand corner of the label.

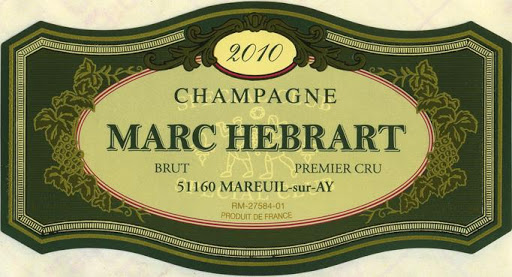

Here is another example of an RM producer, Marc Hebrart. Notice the RM designation listed in the middle of the label.

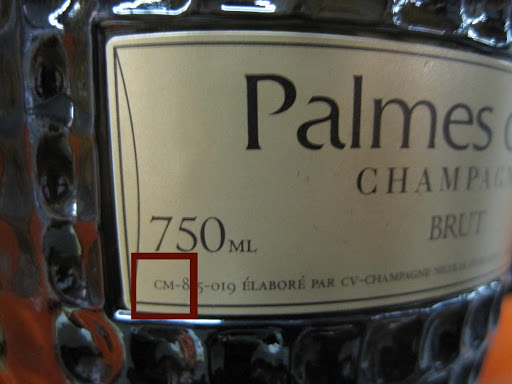

CM (coopérative de manipulation)

A Champagne with the CM abbreviation signifies that a cooperative cellar produced the wine with grapes sourced from its member growers. Perhaps the most famous CM brand is Champagne Nicolas Feuillatte, which sources its grapes from more than 4,500 growers and creates a wide array of blends with fruit from across the region. Note the term CM listed on the label of the brand’s memorable prestige cuvee, Palmes d’Or.

Please keep in mind that these classifications are not qualitative ones. There are great NMs, mediocre CMs, and lackluster RMs. There are also a few other designations to recognize, although they are not often found in the United States.

SR (société de récoltants): This abbreviation refers to an association of grape growers, often family members, who share a winemaking facility, but produce wine under their own labels and are not part of a cooperative.

RC (récoltant coopérateur): An RC producer is a cooperative member who sells a wine produced by the co-op, but under its own name and label.

MA (marque auxiliaire or marque d’acheteur): Essentially, MA signifies a “brand name,” one that is not owned by the grower or producer of the wine, but rather a supermarket, hotel, or restaurant chain. MA brands are commonly referred to as BOBs, or “buyer’s own brand,” as well as “private labels.”

ND (négociant distributeur): A wine merchant who markets Champagne under its own name gets the ND abbreviation.

Now that we’ve discussed the different producer categories, stay tuned for Part II of our Champagne survey, which will consider the distinct flavor profiles offered by wines of the region. In the meantime, visit us at Paul Marcus Wines, where we feature a wide variety of grower-producer Champagne from the likes of Georges Laval, Pierre Moncuit, and Ulysse Collin, as well as offerings from the esteemed NM producer Jacquesson among many others.

This classic, saffron-infused version of paella is the most traditional variant, usually including some combination of chicken, rabbit, duck, beans, peppers, and garlic. Earthy and aromatic, with savory and spicy notes, mencía, a red grape most commonly from Galicia in northwest Spain, would be a wonderful partner with this full-flavored meal. (You’ll want to avoid anything overly tannic.)

This classic, saffron-infused version of paella is the most traditional variant, usually including some combination of chicken, rabbit, duck, beans, peppers, and garlic. Earthy and aromatic, with savory and spicy notes, mencía, a red grape most commonly from Galicia in northwest Spain, would be a wonderful partner with this full-flavored meal. (You’ll want to avoid anything overly tannic.)