The Roero

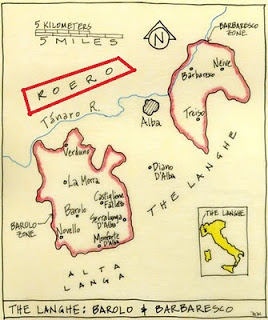

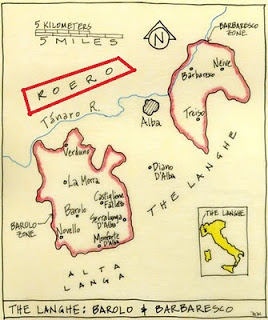

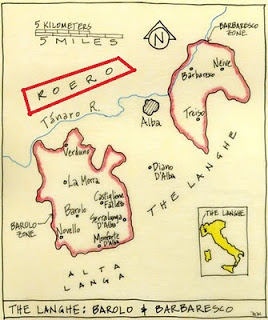

On a clear afternoon in southern Piemonte, the narrow walkway around the tower of Barbaresco gives a breathtaking view of Italy’s greatest winegrowing territory. Directly around and below you are the Barbaresco zone vineyards. You look southwest out over the towers of Alba to the Barolo zone – the village of La Morra perched high, and the castle of Barolo a little beyond. You’re standing in and looking at the Langhe, a region that includes the hilly zones of Barbaresco, Barolo, and the Alta Langa farther south.

On a clear afternoon in southern Piemonte, the narrow walkway around the tower of Barbaresco gives a breathtaking view of Italy’s greatest winegrowing territory. Directly around and below you are the Barbaresco zone vineyards. You look southwest out over the towers of Alba to the Barolo zone – the village of La Morra perched high, and the castle of Barolo a little beyond. You’re standing in and looking at the Langhe, a region that includes the hilly zones of Barbaresco, Barolo, and the Alta Langa farther south.

Train your gaze northwest, across the Tanaro River, and you’ll see a set of hills with a different name – the Roero. (Head there at dusk and you can look back at the Barbaresco tower in a majestic, brooding vista that Fred Seidman captured in one of the photographs hanging in our wine shop.)

The Roero hills, like those in the Langhe, are blanketed with vineyards – as well as orchards, fields, and truffle-yielding woods. While less well known than the Langhe, despite its proximity and equally long winegrowing tradition. Geography and reputation conspire to draw most visitors south and leave the Roero hills looming behind. “Geography” is the Tanaro River valley and the Asti-Alba road that runs through it. Together, the valley and road make a beeline for Alba. “Reputation” is the pull of the storied vineyards and cantinas of Barolo – pilgrimage destination for wine-lovers and beneficiary of the majority of the area’s tourism.

And yet, the Roero yields what is arguably Piemonte’s greatest white wine (Roero Arneis), Barbera of quality equal to the Langhe’s, and excellent Nebbiolo – often at prices that are a notch below Langhe wines of comparable quality. It’s also a great place to stay, eat, taste wines, walk, and bicycle. (More on those activities later in this newsletter!)

Arneis

An indigenous white grape variety called Arneis is the Roero’s wine calling card. A little of it grows elsewhere, but it’s ubiquitous in the Roero, and even people in the Langhe agree that the sandy soils there make the best terroir for Arneis. Until the end of the 1970s, Roero winemakers used Arneis primarily for blending with Nebbiolo – a pinch of Arneis softens Nebbiolo’s notoriously hard tannins and thus yields a slightly softer, younger-drinking wine. Then a few dedicated producers such as Bruno Giacosa and Cerretto showed what Arneis vinified by itself as a white wine could do, and the Arneis craze was on.

DOC / DOCG

Roero Arneis became a DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata – a wine of controlled origin and grape variety) in 1989. Just this year, it was elevated to DOCG status (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita – a designation usually reserved for the best regional wine types).

Roero Arneis is one of those remarkable Italian white wines that combine ample body with a crisp, refreshing quality. It smells of fruits and flowers, but then don’t most white wines? There’s a deeper core in there, like the richness of honey but without its sweetness. And then there’s a smoky note (from the grape and the terroir, not from oak), plus a minerally vein that runs through all the best white wines. Like so many excellent but less common wine types, Roero Arneis is hard to describe but easy to like.

Roero Arneis We Carry

To find out for yourself, take home a bottle of Marco Porello Roero Arneis ‘Camestrì’ 2003 ($11.99) or Matteo Correggia Roero Arneis 2003 ($16.50), or try a glass of Cascina Ca’ Rossa Roero Arneis ‘Merica’ 2003 at the Eccolo dinner on Monday night. All of these wines – and especially Corrregia’s – show the richness and weight of the 2003 vintage, with plenty of aromatic appeal. The 2004 bottlings of these and other Roero Arneis will be arriving soon, and they promise amazing aromatic freshness and lighter palate profiles.

Roero Arneis is a satisfying aperitivo and goes great with most antipasti, including the fishier, anchovy-laden dishes that are so favored by the Piemontese. Really, it’s hard to imagine any lighter fare, including summer pastas and salads, that Roero Arneis wouldn’t go well with.

Barbera

Regular readers of this newsletter may remember my encomium to Barbera in the March 2003 newsletter – it remains a favorite everyday red wine for most of the PMW staff and quite a few of our customers. What I’ve noticed since then, however, is how many of our best-selling Barberas come from the Roero. That’s partly because they tend to have high quality-to-price ratios, and partly because they just taste so damned good!

Much of the Roero is steep hills composed of sandy soils. Steep hills are good for ripening, and sandy soils often give wines an extra dimension of aromatic beauty. The Langhe may make heftier Barbera, but here they excel at producing lovely Barberas. Or, you can ignore these subtle distinctions and just enjoy drinking them.

DOC

Barbera grown in the Roero falls in the Barbera d’Alba DOC (“Barbera from around the town of Alba”), as does most of the Barbera from Barolo and Barbaresco. So you often can’t tell from the label whether a particular Barbera d’Alba is from the Roero or the Langhe, unless you happen to know where the producer or his village is located.

Roero Barbera We Carry

Our best-selling Barbera without a doubt is Filippo Gallino’s Barbera d’Alba 2003 ($11.99). If there is a better pizza-pasta-lasagna wine in the world, I’ve yet to find it. It has that dark-cherry-and-berry Barbera sappiness, with a hint of pepper and menthol to keep things interesting and snappy acidity in the finish to keep the wine refreshing. As our sign in the store says, this is bodacious Barbera.

We’ve got two other Roero Barberas in the store at the moment: Cascina Ca’ Rossa Barbera d’Alba 2003 ($15) and Cascina Val del Prete Barbera d’Alba ‘Serra de’ Gatti’ 2003 ($16). These are slightly more concentrated, complex, and longer on the palate than the Gallino. Both are irresistible.

It’s also worth noting that 2003 has turned out to be the Barbera Vintage. All of Europe sweltered during the summer of ’03, and many wines from the vintage don’t quite have the snappy freshness that we love. But Barbera’s naturally high acidity kept the wines fresh and vivid, and the extra heat only deepened their irresistible fruit.

Although the Roero is a great source of fresh, everyday, under-$20 Barbera, some producers are showing that they can make serious, barrique-aged Barbera to rival those from the Langhe. (See the March 2003 newsletter article referenced above for more information about this style of Barbera.) On Monday night at Eccolo, we’ll be drinking the Cascina Ca’ Rossa Barbera d’Alba ‘Mulassa’ 2001, a single-vineyard Barbera that Angelo Ferrio aged for 18 months in barrique. One of the benchmark “serious” Roero Barberas is Cascina Val del Prete’s Barbera d’Alba ‘Carolina’. (At a certain tony restaurant in Los Angeles, the staff know Mario Roagna, the proprietor of Cascina Val del Prete, as “Mr. Carolina”.) The 2001 is long gone, and Mario didn’t make any in 2002, but keep an eye out for the 2003 vintage – it will be wickedly good.

What should you drink Roero Barbera with? What shouldn’t you drink Roero Barbera with? All things tomato-y. Antipasti. Anchovies and especially bagna caoda (the anchovy-based dipping sauce that serves as the ketchup of Piemonte). Chicken. Sausages. It even works with moderately spicy food and some Asian dishes.

Nebbiolo

Nebbiolo is the great wine grape variety of Piemonte, as our September 2004 newsletter describes. Although Barolo and Barbaresco are the most famous incarnations of Nebbiolo, Roero Nebbiolo has been held in high esteem since at least the 17th century. More importantly, there’s some genuinely excellent Nebbiolo being made in the Roero right now!

DOC / DOCG

As in the Langhe, the Roero bottles two kinds of Nebbiolo. The first is a fresh, younger-drinking wine usually called simply Nebbiolo d’Alba or Langhe Nebbiolo. (As with Barbera d’Alba, the Nebbiolo d’Alba DOC doesn’t tell you where in the region around Alba the Nebbiolo grapes come from – it could be either or). The more serious, structured wine is called simply Roero. Like Roero Arneis, the Roero DOC is being elevated to a DOCG this year. So “Roero Arneis” DOCG is white wine made from Arneis, and “Roero” DOCG is red wine made from Nebbiolo. Got it?

The region has already made a reputation for itself with Arneis. Whether it will take its place alongside Barolo and Barbaresco as the third great Piemontese appellation depends entirely on what the producers do with Nebbiolo – and on whether the elevation to DOCG status causes critics to pay more attention to what producers are doing.

For now, we can ignore all of that and simply thank Bacchus (and Angelo Ferrio) for the Cascina Ca’ Rossa Langhe Nebbiolo 2003 ($16). This is what young Nebbiolo should taste like – fresh but sophisticated, supple but with enough tannin to do meat justice. As is true with Barbera, the sandy soils of the Roero lend a particularly pretty aromatic profile to Roero Nebbiolos like this one.

Marco Porello’s Roero ‘Torretta’ 2001 was one of our favorite Nebbiolos in the store about a year ago. The 2003 vintage of this wine should arrive before too long, and judging from how it tasted in Piemonte in March, it will be another winner.

Roero Nebbiolo We Carry

Angelo’s Cascina Ca’ Rossa Roero ‘Audinaggio’ 2001 ($38) is excellent Nebbiolo from an excellent producer in an excellent vintage. This wine impressed me mightily at a lunch in March, and you’ll have the opportunity to drink it, as well as the 1999 vintage, at Eccolo on Monday 20 June.

Three other “serious” Roero Nebbiolos are worthy of mention, even though we don’t have all of them in the store at the moment. Filippo Gallino’s Roero Superiore 2001 was still in tank when I tasted it in March, but it had all the makings of a superb wine. Mario Roagna makes two impressive single-vineyard Nebbiolo wines: Cascina Val del Prete Nebbiolo d’Alba ‘Vigna di Lino’ ($38 for the 2001 vintage) and Cascina Val del Prete Roero. Both are widely acknowledged as being among the top Roero wines – we’ll be getting these in as new vintages when it becomes available.

Meat and game are the classic matches with Nebbiolo. Lamb and Nebbiolo play well together, and I particularly like gamy birds such as pigeon with Roero. See our September 2004 newsletter for more suggestions.

Birbét

After all this talk of “serious” wines, it seems suitable to end with a purely fun wine. Birbét is the Roero’s version of Brachetto d’Acqui – a light, low-alcohol, slightly sweet, frizzante red wine for after dinner. (It’s a red analogue of Moscato d’Asti, made from the Brachetto grape rather than from Moscato.) “Birbét” is a Piemontese word meaning lively, fun, and a little bit mischievous – you’ve been warned! It smells of strawberries, rose petals, and cinnamon. Midwestern grandmas and sommeliers love it. It goes down easy and doesn’t intoxicate (much), but still makes everything and everyone look prettier.

The one that we have in the store and that Eccolo pours is Cascina Ca’ Rossa Birbét 2003 ($19). Drink some and watch your life improve.

On a clear afternoon in southern Piemonte, the narrow walkway around the tower of Barbaresco gives a breathtaking view of Italy’s greatest winegrowing territory. Directly around and below you are the Barbaresco zone vineyards. You look southwest out over the towers of Alba to the Barolo zone – the village of La Morra perched high, and the castle of Barolo a little beyond. You’re standing in and looking at the Langhe, a region that includes the hilly zones of Barbaresco, Barolo, and the Alta Langa farther south.

On a clear afternoon in southern Piemonte, the narrow walkway around the tower of Barbaresco gives a breathtaking view of Italy’s greatest winegrowing territory. Directly around and below you are the Barbaresco zone vineyards. You look southwest out over the towers of Alba to the Barolo zone – the village of La Morra perched high, and the castle of Barolo a little beyond. You’re standing in and looking at the Langhe, a region that includes the hilly zones of Barbaresco, Barolo, and the Alta Langa farther south.