At the start of June, Chad and I hosted a Loire Valley-inspired dinner with our friends at the Wolf. We were joined by many loyal shop customers along with a handful of industry veterans—all equally eager to embark on this journey. We had no idea there would be such immediate interest in the event, and the high demand meant that our meal was a slightly snug fit, which only emphasized the intimate, friendly atmosphere.

And the food! From the first bite, we knew that we were in for a delight. The potato pavé was a little square of joy leaving us all craving more—crisped on the outside, the layers of potato sliding apart in the mouth. It was absolute perfection, especially when paired with Domaine de la Paleine Saumur Brut.

And the food! From the first bite, we knew that we were in for a delight. The potato pavé was a little square of joy leaving us all craving more—crisped on the outside, the layers of potato sliding apart in the mouth. It was absolute perfection, especially when paired with Domaine de la Paleine Saumur Brut.

Already off to a great start, the most unusual and thought-provoking course was the “surf & turf” steak tartare served on top of octopus carpaccio with herbs, all wrapped together with a most luxurious olive oil. Shocking, but highly effective! This was paired with Paul Prieur’s Sancerre ‘Pieuchaud Silex,’ a focused, mineral, chalky sauvignon blanc, as well as his Sancerre Rouge, a lifted, delicate pinot noir boasting red fruit and dried earth that did not overpower the food.

As the evening continued, chef Yang Peng continued to impress. With the two cabernet francs—the 2015 Domaine de la Chevalerie Bourgueil ‘Bretêche’ and the 2021 Bernard Baudry Chinon ‘La Croix Boissée’—she served the most melt-in-your-mouth pork belly and a spiced beef brisket (garnished with shaved jalapeño and a kiss of basil). It takes such skill not only to pair the wines but to elevate them; both of these wines tasted better than they ever have!

One goal of the dinner was to disrupt the expected serving progression of lightest wines to richest. Not only did we have the Sancerre blanc and rouge served side by side, but we also toggled from cab franc to chenin blanc and then back to red, before moving on to dessert wine. We also snuck in a brief cheese “interlude” to refresh the palate and the mind—an ash-rubbed goat’s milk served with an aged Muscadet (the 2015 Huchet Muscadet Monnieres Saint-Fiacre). It was a brilliant choice.

One of my favorite wine duos was a “battle” of chenin vs. chenin: the 2019 Thibaud Boudignon Savennières ‘Clos de Frémine’ against the 2020 Domaine Belargus Anjou Noir. At first, these two wines were vastly different, the Belargus being the richer, nuttier, more generous wine (a product of the warmer vintage and élevage in slightly more new oak), and the Boudignon being stony, mineral, and filled with mouthwatering acid. But as they sat in the glass, the Boudignon gained richness, and the Belargus grew focused—both wines coming together toward the center.

After the plethora of wines on the menu, Chad surprised the group with two bonus selections from his cellar: Boudignon’s 2013 Savennières (a blended wine from the estate’s early days) and the 2013 Domaine du Collier Saumur Blanc ‘La Charpentrie.’ Again, the two wines couldn’t have been more contrasted at the outset—and from two winemakers that are very close friends!

The night ran somewhat longer than expected, as we were all reluctant to depart such a warm, welcoming place. We eventually pulled ourselves away and made our way home—sleepy, content, and dreaming of France…

— Ailis Peplau

As we settled in, we mused on chenin’s relationship to two other great white wines of France: Champagne and white Burgundy. Loire chenin blanc, we realized, serves less often as a celebratory or special-occasion wine, and we wondered why that is.

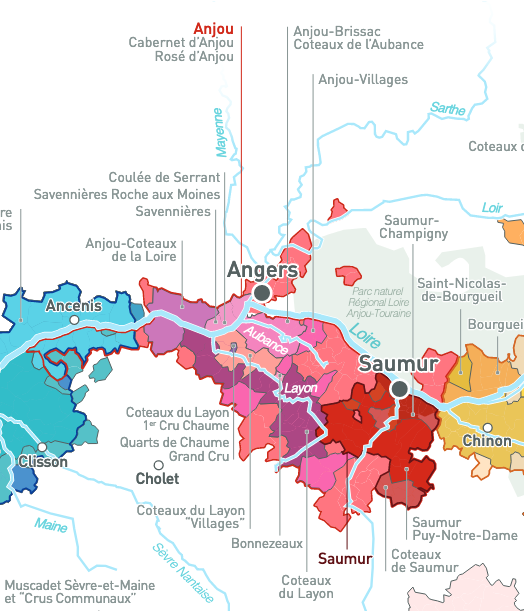

As we settled in, we mused on chenin’s relationship to two other great white wines of France: Champagne and white Burgundy. Loire chenin blanc, we realized, serves less often as a celebratory or special-occasion wine, and we wondered why that is. Our first flight included current vintages of two longtime PMW denizens: the 2019 François Chidaine Montlouis ‘Clos du Breuil’ ($39) and 2018 Domaine aux Moines Savennières ‘Roche aux Moines’ ($42). Both were as comfortable as a favorite, old wool sweater. “Wooliness,” of course, is a common descriptor for the texture and lanolin notes of richer chenin blanc. “Honeyed minerality” and “wet concrete in November” also fit the bill. Yes, there’s a richness of fruit and mouth feel, but it’s tempered by chenin’s minerality and big-time acidity. One might also notice the red-fruit flavors in some of these wines. (Funny how that can happen in white wines!)

Our first flight included current vintages of two longtime PMW denizens: the 2019 François Chidaine Montlouis ‘Clos du Breuil’ ($39) and 2018 Domaine aux Moines Savennières ‘Roche aux Moines’ ($42). Both were as comfortable as a favorite, old wool sweater. “Wooliness,” of course, is a common descriptor for the texture and lanolin notes of richer chenin blanc. “Honeyed minerality” and “wet concrete in November” also fit the bill. Yes, there’s a richness of fruit and mouth feel, but it’s tempered by chenin’s minerality and big-time acidity. One might also notice the red-fruit flavors in some of these wines. (Funny how that can happen in white wines!)

Although the 2012s are long gone, fear not: We have in stock the 2018 Boudignon Anjou Blanc ($45) and 2017 Boudignon Anjou Blanc ‘a François(e)’ ($75). Like so much white Burgundy and Champagne, these wines are beautiful now, but will handsomely repay aging in your cellar if you’re so inclined. (We also have Boudignon’s three magisterial bottlings of 2019 Savennières: ‘La Vigne Cendrée,’ ‘Clos de Frémine,’ and ‘Clos de la Hutte.’)

Although the 2012s are long gone, fear not: We have in stock the 2018 Boudignon Anjou Blanc ($45) and 2017 Boudignon Anjou Blanc ‘a François(e)’ ($75). Like so much white Burgundy and Champagne, these wines are beautiful now, but will handsomely repay aging in your cellar if you’re so inclined. (We also have Boudignon’s three magisterial bottlings of 2019 Savennières: ‘La Vigne Cendrée,’ ‘Clos de Frémine,’ and ‘Clos de la Hutte.’) Our newest chenin blanc discovery is Domaine Belargus, a new Loire Valley estate with a single focus on chenin blanc and its different terroirs in the mid Loire Valley, including Anjou. (“Belargus” is a rare species of brilliantly blue-winged butterfly that inhabits the vineyards.) We have the 2019 Domaine Belargus ‘Anjou Noir’ ($36) (the “Noir” refers not to the color of the grapes, but to the dark color of the schist-and-shale-rich soils in the western half of the Anjou appellation) and the 2018 Domaine Belargus Anjou ‘Ronceray’ ($57), from seven tiny vineyard plots surrounding the Ronceray Abbey. This is most certainly a domaine to investigate now, before collectors get on board and drive up prices.

Our newest chenin blanc discovery is Domaine Belargus, a new Loire Valley estate with a single focus on chenin blanc and its different terroirs in the mid Loire Valley, including Anjou. (“Belargus” is a rare species of brilliantly blue-winged butterfly that inhabits the vineyards.) We have the 2019 Domaine Belargus ‘Anjou Noir’ ($36) (the “Noir” refers not to the color of the grapes, but to the dark color of the schist-and-shale-rich soils in the western half of the Anjou appellation) and the 2018 Domaine Belargus Anjou ‘Ronceray’ ($57), from seven tiny vineyard plots surrounding the Ronceray Abbey. This is most certainly a domaine to investigate now, before collectors get on board and drive up prices.

My absolute favorite examples of Cesanese d’Affile come from Damiano Ciolli and his partner, Letizia Rocchi. The Ciolli family vineyards sit in a natural amphitheater with a southerly exposure and include seven hectares of Cesanese d’Affile, with some of the vines being close to 70 years old. They craft two incredible bottlings, both from 100 percent Cesanese d’Affile: the younger-vine, concrete-aged

My absolute favorite examples of Cesanese d’Affile come from Damiano Ciolli and his partner, Letizia Rocchi. The Ciolli family vineyards sit in a natural amphitheater with a southerly exposure and include seven hectares of Cesanese d’Affile, with some of the vines being close to 70 years old. They craft two incredible bottlings, both from 100 percent Cesanese d’Affile: the younger-vine, concrete-aged

Our journey begins in the south, on the island of Sicily. The volcanic soils of Mt. Etna are home to the nerello mascalese grape, which produces a wonderfully complex and savory style of rosato. These wines tend to be quite dry, aromatic, and bursting with minerality. At PMW, we’ve been enjoying both the Graci Etna Rosato (a bit more focus) and the Terre Nere Etna Rosato (a tad more fruit). From the southern part of the island comes the Due Terre Rosato di Frappato, a bright, floral wine with a striking deep-amber hue.

Our journey begins in the south, on the island of Sicily. The volcanic soils of Mt. Etna are home to the nerello mascalese grape, which produces a wonderfully complex and savory style of rosato. These wines tend to be quite dry, aromatic, and bursting with minerality. At PMW, we’ve been enjoying both the Graci Etna Rosato (a bit more focus) and the Terre Nere Etna Rosato (a tad more fruit). From the southern part of the island comes the Due Terre Rosato di Frappato, a bright, floral wine with a striking deep-amber hue. East of Rome and bordering the Adriatic Sea, the verdant Abruzzo region is the province of the dark-skinned montepulciano grape, which produces a rich, structured style of rosato called Cerasuolo d’Abruzzo. The Ciavolich Cerasuolo d’Abruzzo ‘Fosso Cancelli’ is darker in color than some of the “red” wines that we carry. After 24-36 hours of skin maceration in concrete, this wine is moved to terracotta amphorae for further fermentation and aging, resulting in a wine that is dense, yet still lively–a match for more substantial fare than your typical rosé. Fermented and aged briefly in stainless steel, the low-sulfite Cirelli Cerasuolo d’Abruzzo represents a lighter version of this noteworthy type of rosato.

East of Rome and bordering the Adriatic Sea, the verdant Abruzzo region is the province of the dark-skinned montepulciano grape, which produces a rich, structured style of rosato called Cerasuolo d’Abruzzo. The Ciavolich Cerasuolo d’Abruzzo ‘Fosso Cancelli’ is darker in color than some of the “red” wines that we carry. After 24-36 hours of skin maceration in concrete, this wine is moved to terracotta amphorae for further fermentation and aging, resulting in a wine that is dense, yet still lively–a match for more substantial fare than your typical rosé. Fermented and aged briefly in stainless steel, the low-sulfite Cirelli Cerasuolo d’Abruzzo represents a lighter version of this noteworthy type of rosato. PMW currently stocks three different expressions of Alto Piemonte rosato. The rust-colored Le Pianelle Coste della Sesia Rosato ‘Al Posto dei Fiori’ adds a touch of vespolina and croatina to its nebbiolo foundation, along with just a hint of oak influence. It’s a full-flavored, multifaceted rosato that still manages to be fresh and nimble thanks to ample acidity and a mineral edge. The Antoniolo Gattinara Rosato ‘Bricco Lorella’ undergoes a relatively short maceration (about three hours), and the resulting wine is vibrant and graceful, with vivid red-berry notes.

PMW currently stocks three different expressions of Alto Piemonte rosato. The rust-colored Le Pianelle Coste della Sesia Rosato ‘Al Posto dei Fiori’ adds a touch of vespolina and croatina to its nebbiolo foundation, along with just a hint of oak influence. It’s a full-flavored, multifaceted rosato that still manages to be fresh and nimble thanks to ample acidity and a mineral edge. The Antoniolo Gattinara Rosato ‘Bricco Lorella’ undergoes a relatively short maceration (about three hours), and the resulting wine is vibrant and graceful, with vivid red-berry notes.